If you were in Tunisia in October, you might have caught some of the Morse Code championships this year. If you didn’t make it, you could catch the BBC’s documentary about the event, and you might be surprised at some of the details. For example, you probably think sending and receiving Morse code is only for the elderly. Yet the defending champion is 13 years old.

Teams from around the world participated. There was stiff competition from Russia, Japan, Kuwait, and Romania. However, for some reason, Belarus wins “almost every time.” Many Eastern European countries have children’s clubs that teach code. Russia and Belarus have government-sponsored teams.

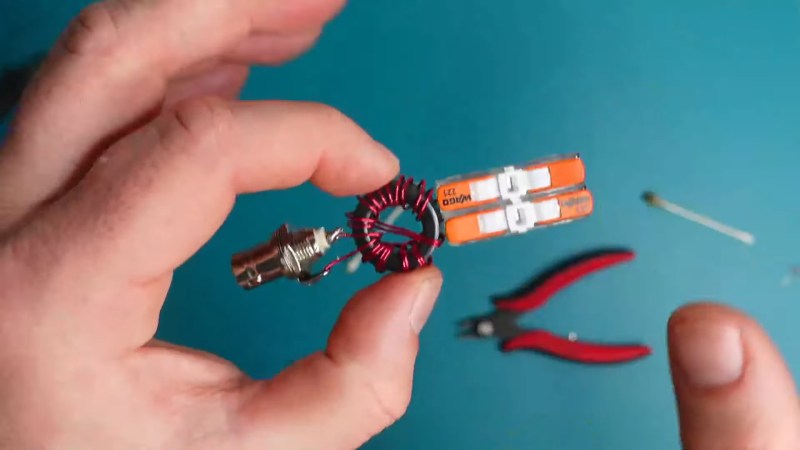

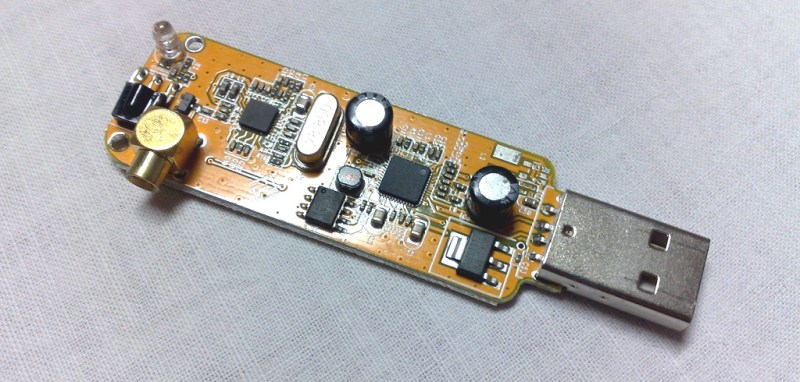

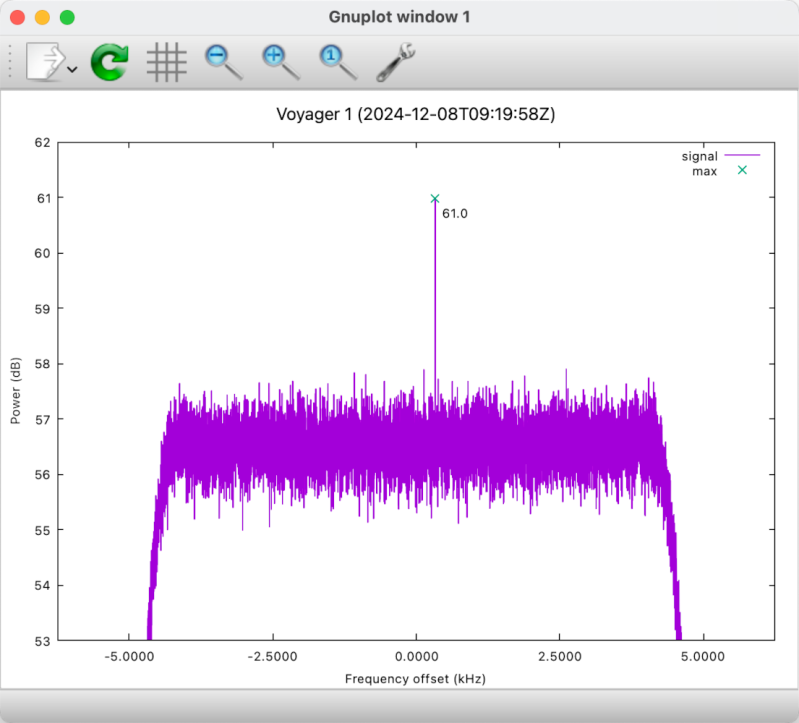

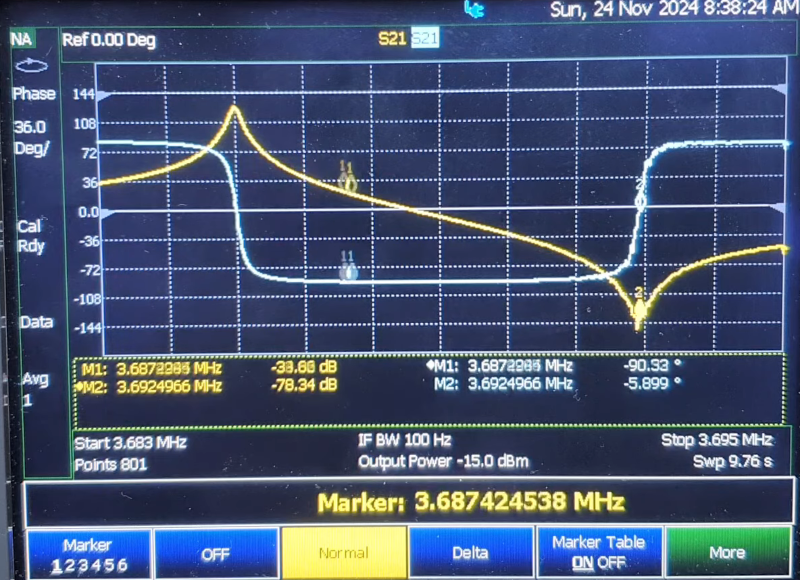

Morse code is very useful to amateur radio operators because it allows them to travel vast distances using little power and simple equipment. Morse code can also assist people who otherwise might have problems communicating, and some assistive devices use code, including a Morse code-to-speech ring the podcast covers.

The speed records are amazing and a young man named [Ianis] set a new record of 1,126 marks per minute. Code speed is a little tricky since things like the gap size and what you consider a word or character matter, but that’s still a staggering speed, which we estimate to be about 255 words per minute. While we can copy code just fine, at these speeds, it sounds more like modem noises.

Learning Morse code isn’t as hard as it sounds. Your computer can help you learn, but in the old days, you had to rely on paper tape.