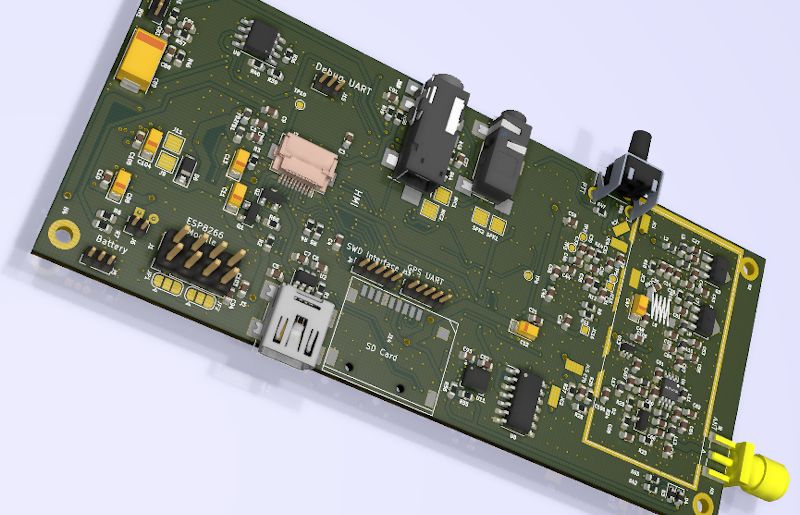

Op 15 november 2018 werd vanaf Kennedy Spacecenter de Es’hail 2 gelanceerd richting een geostationaire baan om de aarde en sinds enige tijd is de satelliet te gebruiken door radiozendamateurs.

Met een downlink op 10 GHz en een uplink op 2,4 GHz is de satelliet door amateurs betrekkelijk eenvoudig te gebruiken. Het blijkt dat het ontvangen van de satelliet eenvoudiger is dan gedacht. Thijs, PE1RLN neemt je graag mee in zijn ervaringen bij het ontvangen van de smalband communicatie.

10GHz omzetten

Het ontvangen van een 10 GHz signaal lijkt heel moeilijk maar is met behulp van wat hulpmiddelen erg eenvoudig. Elke satellietschotel heeft een LNB (low noise blockconverter) die het 10GHz signaal van bijvoorbeeld de Astra satelliet omlaag brengt naar circa 900 MHz, een frequentie die al beter te behappen is. Maar voor ons radiozendamateurs geen gangbare frequentie natuurlijk.

De LNB links op de foto kun je vinden bij Passion Radio en deze transformeert het 10 GHz signaal van de Es’hail naar 432 MHz ! Kijk, dan wordt het interessant.

De LNB is voorzien van een 0,5ppm TCXO voor goede stabiliteit en je krijgt er een bias-tee bij om de LNB te voorzien van spanning. Deze werkt namelijk op 12V via de coax. Bij 12V werkt de LNB op vertikale polarisatie, prima voor de smalband transponder. Bij 14-18V werkt hij horizontaal voor de breedband transponder. Voor € 80 heb je ‘m thuisbezorgd binnen een paar dagen.

De IC-9700 transceiver van Icom kan op de antenne-aansluiting ook 12V tijdens RX afgeven, dan heb je de bias-tee niet nodig.

De lokale oscillator in de LNB werkt op 10.057 MHz dus bijvoorbeeld het PSK baken op 10.489,750 MHz ontvang je straks op 432,750 MHz.

Schotel

Schotels zijn voor shoarma én om satellieten te ontvangen. Thijs had nog een 35cm campingschotel liggen en die bleek prima te functioneren voor ontvangst! Dus investeer niet in grote radiotelescopen, 35cm volstaat. Zorg dat je een stevig statief hebt want het uitrichten komt een beetje precies.

De LNB wordt voorop gemonteerd en wel zodanig dat deze een “skew” heeft van -15,9 graden. Dat betekent dat de LNB gekanteld wordt met de wijzers van de klok mee als je over de LNB heen naar de schotel kijkt. Dat heeft te maken met de kanteling (skew) van de polarisatie van de satelliet zelf. Hoe beter de skew is afgeregeld, hoe sterker het signaal.

Aansluiten

De LNB en de bias-tee zijn voorzien van F-connectoren, zeer gebruikelijk bij satelliet-TV. Thijs heeft achter op de schotel een BNC aansluiting gemaakt en heeft de bias-tee in een kastje ingebouwd met BNC-connectoren. De impedantie klopt niet helemaal en dat levert verlies op maar de LNB geeft zo’n keihard signaal af dat je dat prima kunt permitteren. Op de bias-tee zit zelfs een attenuator die het signaal dempt en die heb je zeker nodig.

De bias-tee komt dus tussen LNB en ontvanger (tenzij je ontvanger al 12V op de coax heeft) en dan stem je af op 432,750 MHz.

De bias-tee komt dus tussen LNB en ontvanger (tenzij je ontvanger al 12V op de coax heeft) en dan stem je af op 432,750 MHz.

Met het stelknopje in de deksel kun je de attenuation instellen. Aangezien de coax kort is en de LNB een hard signaal geeft, kun je deze best zo instellen dat bij een normale RF gain je waterfall weinig ruis laat zien zodat signalen goed zichtbaar zijn. Dit is handig bij het uitrichten.

Uitrichten van de schotel

Stel de schotel bijna vertikaal en richt de arm van de LNB richting het zuiden. Draai vervolgens 26 graden naar het oosten (tegen wijzers van de klok in dus).

Stel de schotel bijna vertikaal en richt de arm van de LNB richting het zuiden. Draai vervolgens 26 graden naar het oosten (tegen wijzers van de klok in dus).

Kijk voor de duidelijkheid op www.dishpointer.com voor precieze uitrichting van je schoteltje. Een schotel met elevatie-gradenboog op de achterkant is ook gemakkelijk om de beginpositie te vinden.

Als je de ontvanger aanzet met een waterfall display dan zie je bij een juiste uitrichting allemaal signalen opdoemen rond 432,750 MHz. Je zult merken dat de afstelling van de schotel niet ultra-precies is maar als je de RF gain terugdraait dan kun je aan de hand van de S-meter de maximale uitslag zoeken met de schotel.

De signalen zijn zeer goed te nemen, alsof het lokale SSB signalen zijn. En dat op een afstand van 35.786 km !!! Had je niet gedacht he?

De signalen zijn zeer goed te nemen, alsof het lokale SSB signalen zijn. En dat op een afstand van 35.786 km !!! Had je niet gedacht he?

Je ziet dat de signalen niet heel ver boven de ruis uit komen maar de S/R ratio is prima. De LNB versterkt ook ruis en alleen een grotere schotel maakt het signaal nog schoner. Maar dat levert geen beter signaal op, dit is namelijk al prima.

Luisteren!

Nu kun je met de ontvanger over de hele band draaien, van 432,500 MHz tot 433,000 MHz. Je hoort onderin CW en in het midden de SSB signalen volgens onderstaand bandplan:

Onderstaand een plot van de dekking van de satelliet: