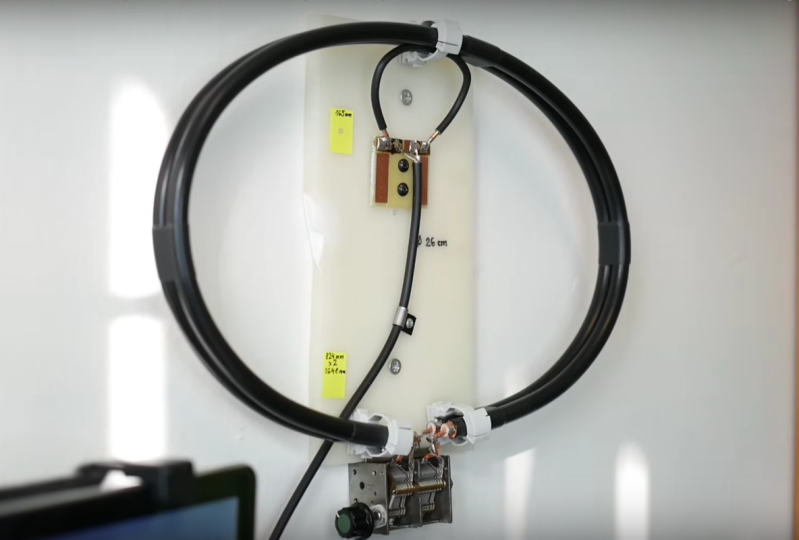

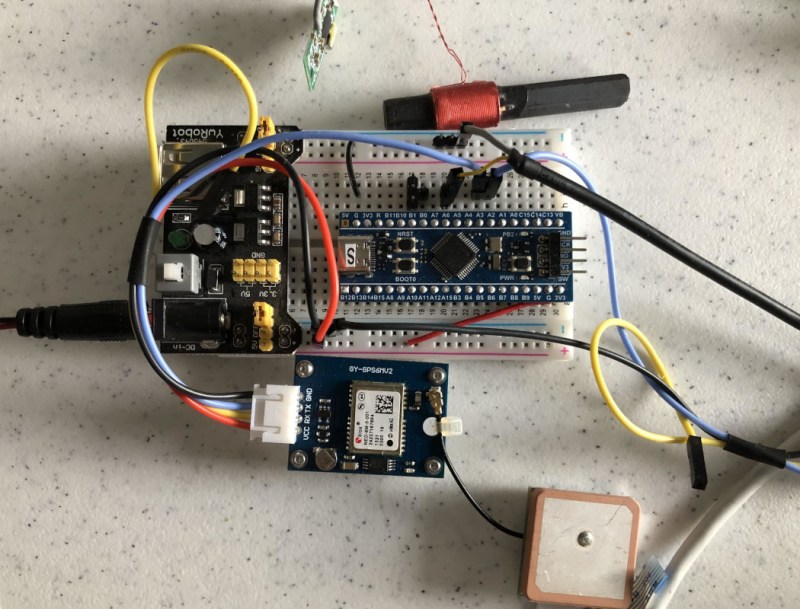

Something that all radio amateurs encounter sooner or later is the subject of impedance matching. If you’d like to make sure all that power is transferred from your transmitter into the antenna and not reflected back into your power amplifier, there’s a need for the impedance of the one to match that of the other. Most antennas aren’t quite the desired 50 ohms impedance, so part of the standard equipment becomes an antenna tuner — an impedance matching network. For high-power hams these are big boxes full of chunky variable capacitors and big air cored inductors, but that doesn’t exclude the low-power ham from the impedance matching party. [Barbaros Aşuroğlu WB2CBA] has designed the perfect device for them: the credit card ATU.

The circuit of an antenna tuner is simple enough, two capacitors and an inductor in a so-called Pi-network because of its superficial resemblance to the Greek letter Pi. The idea is to vary the capacitances and inductance to find the best match, and on this tiny model it’s done through a set of miniature rotary switches. There are a set of slide switches to vary the configuration or switch in a load, and there’s even a simple matching indicator circuit.

We like this project, in that it elegantly provides an extremely useful piece of equipment, all integrated into a tiny footprint. It’s certainly not the first ATU we’ve brought you.

Thanks [ftg] for the tip!