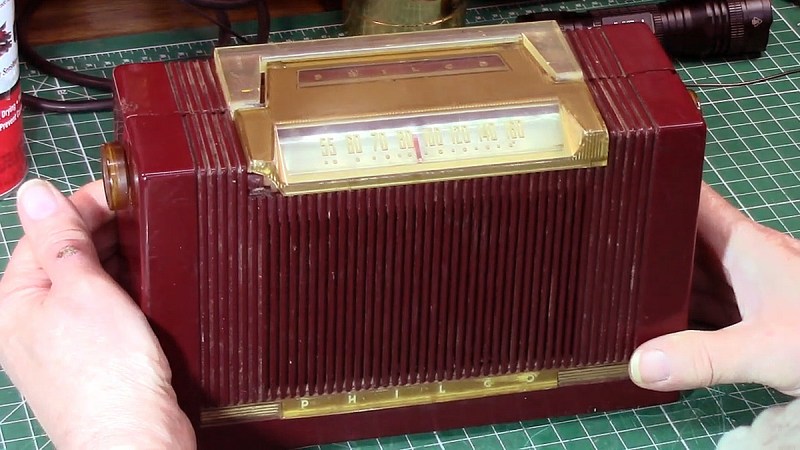

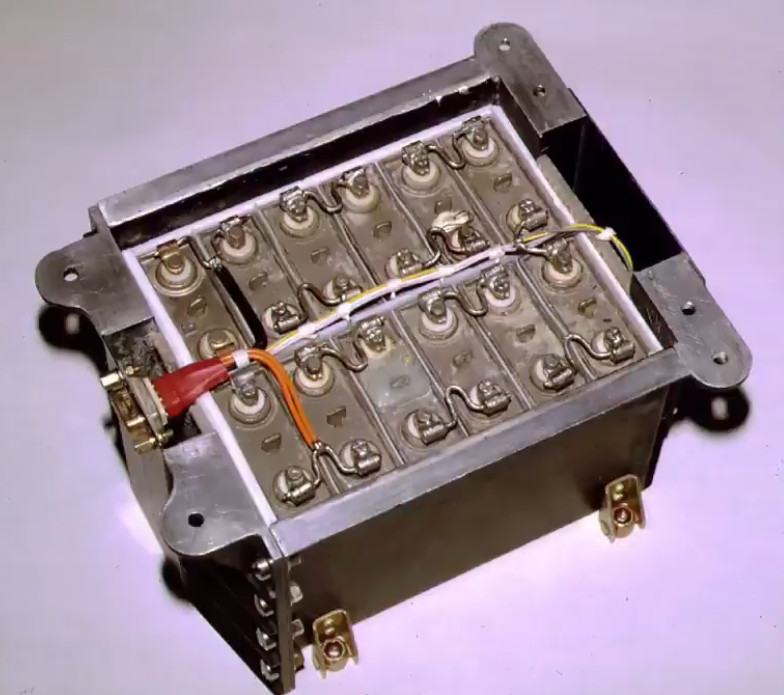

When the AMSAT-OSCAR 7 (AO-7) amateur radio satellite was launched in 1974, its expected lifespan was about five years. The plucky little satellite made it to 1981 when a battery failure caused it to be written off as dead. Then, in 2002 it came back to life. The prevailing theory being that one of the cells in the satellites NiCd battery pack, in an extremely rare event, shorted open — thus allowing the satellite to run (intermittently) off its solar panels.

In a recent video by [Ben] on the AE4JC Amateur Radio YouTube channel goes over the construction of AO-7, its operation, death and subsequent revival are covered, as well as a recent QSO (direct contact).

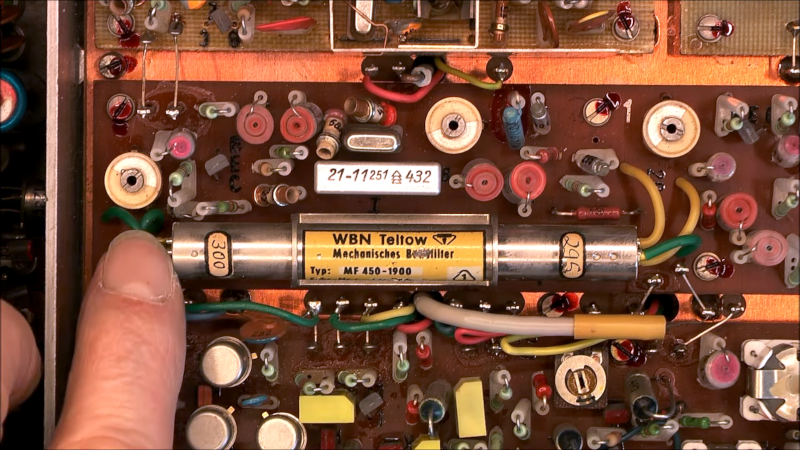

The solar panels covering this satellite provided a grand total of 14 watts at maximum illumination, which later dropped to 10 watts, making for a pretty small power budget. The entire satellite was assembled in a ‘clean room’ consisting of a sectioned off part of a basement, with components produced by enthusiasts associated with AMSAT around the world. Onboard are two radio transponders: Mode A at 2 meters and Mode B at 10 meters, as well as four beacons, three of which are active due to an international treaty affecting the 13 cm beacon.

Positioned in a geocentric LEO (1,447 – 1,465 km) orbit, it’s quite amazing that after 50 years it’s still mostly operational. Most of this is due to how the satellite smartly uses the Earth’s magnetic field for alignment with magnets as well as the impact of photons to maintain its spin. This passive control combined with the relatively high altitude should allow AO-7 to function pretty much indefinitely while the PV panels keep producing enough power. All because a NiCd battery failed in a very unusual way.