It’s easy to dismiss radio as little more than background noise while we drive. At worst you might even think it’s just another method for advertisers to peddle their wares. But in reality it’s a snapshot of the culture of a particular time and place; a record of what was in the news, what music was popular, what the weather was like, basically what life was like. If it was important enough to be worth the expense and complexity of broadcasting it on the radio, it’s probably worth keeping for future reference.

It’s easy to dismiss radio as little more than background noise while we drive. At worst you might even think it’s just another method for advertisers to peddle their wares. But in reality it’s a snapshot of the culture of a particular time and place; a record of what was in the news, what music was popular, what the weather was like, basically what life was like. If it was important enough to be worth the expense and complexity of broadcasting it on the radio, it’s probably worth keeping for future reference.

But radio is fleeting, a 24/7 stream of content that’s never exactly the same twice. Yet while we obsessively document music and video, nobody’s bothering to record radio. You can easily hop online and watch a TV show that originally aired 50 years ago, but good luck finding a recording of what your local radio station was broadcasting last week. All that information, that rich tapestry of life, is gone and there’s nothing we can do about it.

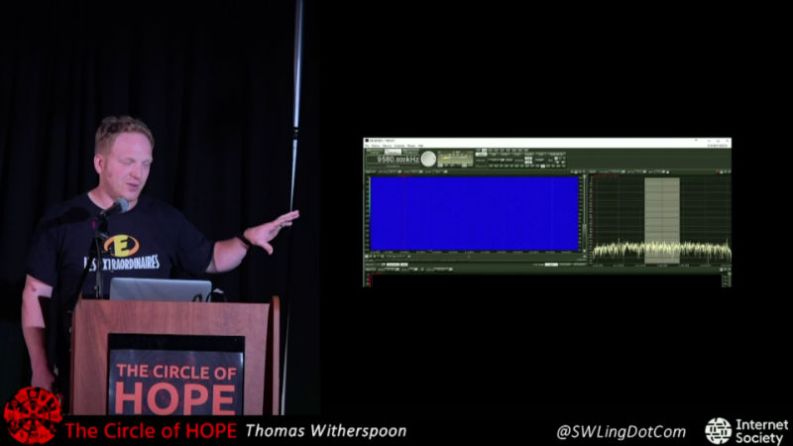

Or can we? At HOPE XII, Thomas Witherspoon gave a talk called “Creating a Radio Time Machine: Software-Defined Radios and Time-Shifted Recordings”, an overview of the work he’s been doing recording and cataloging the broadcast radio spectrum. He demonstrated how anyone can use low cost SDR hardware to record, and later play back, whole chunks of the AM and shortwave bands. Rather than an audio file containing a single radio station, the method he describes allows you to interactively tune in to different stations and explore the airwaves as if it were live.

Modern Take on a Classic Technique

You might think that such radio trickery is a product of modern hardware and software, but in fact the methods Thomas and his group of radio archivists use have considerably more retro beginnings. As far back as the 1980’s DXers, radio hobbyists that look specifically for distant signals, found that if they connected the intermediate frequency (IF) output of their radio to a VCR they could capture whatever their antenna was picking up for later analysis. When the tape was played back through the antenna port of the radio, they could tune to individual frequencies and search for hard to hear signals.

Of course the utility of this method wasn’t limited to just weak signals. It allowed radio operators to do things that would otherwise be impossible, like going back and listening to different news broadcasts that were aired at the same time. A few DXers realized there was a potential historical value to such recordings, and some of these early tapes were saved and wound up becoming part of the collection Thomas has been building and offering up as a podcast.

The modern version of this technique replaces the AM or shortwave receiver with any one of a number of affordable SDR devices, and the VCR has become a piece of software that can dump the SDR’s output to a file. This file can then be loaded up in a compatible SDR interface program, such as HDSDR, in place of an actual radio.

Storing History

Thomas envisions a future where researchers will be able to sit down at a kiosk and browse through the radio broadcasts from a given time and place, the same way a microfilm machine is used to look at a newspaper from decades past. But while making these recordings is now cheaper and easier than ever before, there are still logistical issues that need to be solved before that can happen. Chief among them: how do you store it all?

Thomas mentions that a single day’s recording of the AM broadcast band will result in roughly 1 TB of data. Potentially some compression scheme could be developed which would scan the recordings to isolate the viable signals and delete the rest. Another approach would be a sort of ring buffer arrangement, where the system only retains the last few days of recordings unless the user commits them to long-term storage. If something deemed worthy of future study occurs, the ring buffer could be moved to permanent storage so the event as well as the preceding time could be preserved for historical purposes.

Until then, Thomas and his team will keep on recording during noteworthy events. As an example, they made extensive spectrum recordings during the 2016 US Presidential elections, believing it will be a moment future generations will likely want to have as much information on as possible.