How do you get images downlinked from 30 km up? Hams might guess SSTV — slow scan TV — and that’s the approach [desafloinventor] took. If you haven’t seen it before (no pun intended), SSTV is a way to send images over radio at a low frame rate. Usually, you get about 30 seconds to 2 minutes per frame.

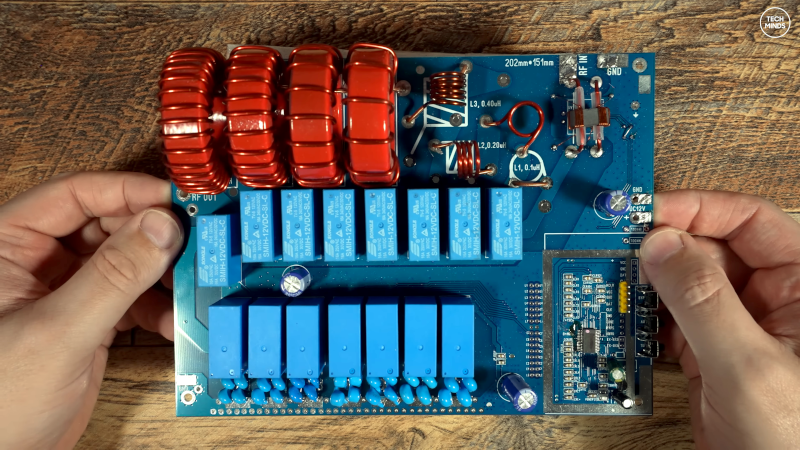

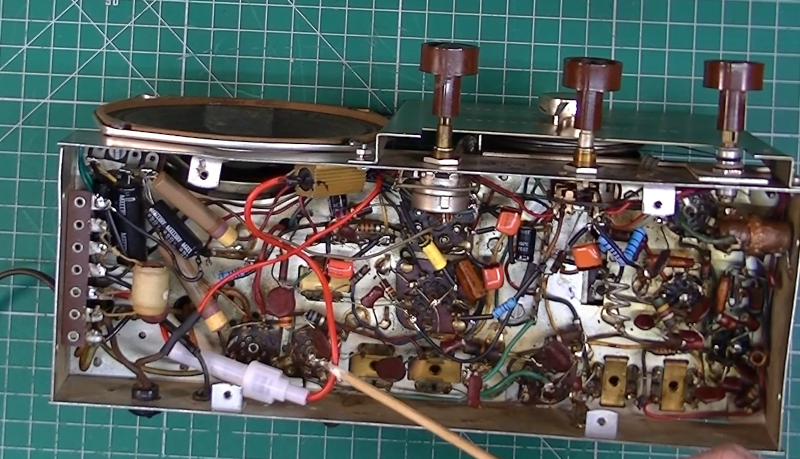

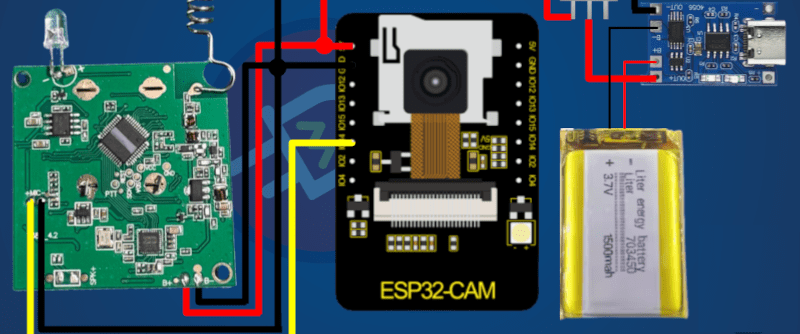

The setup uses regular, cheap walkie-talkies for the radio portion on a band that doesn’t require a license. The ESP32-CAM provides the processing and image acquisition. Normally, you don’t think of these radios as having a lot of range, but if the transmitter is high, the range will be very good. The project steals the board out of the radio to save weight. You only fly the PC board, not the entire radio.

If you are familiar with SSTV, the ESP-32 code encodes the image using Martin 1. This color format was developed by a ham named [Martin] (G3OQD). A 320×256 image takes nearly two minutes to send. The balloon system sends every 10 minutes, so that’s not a problem.

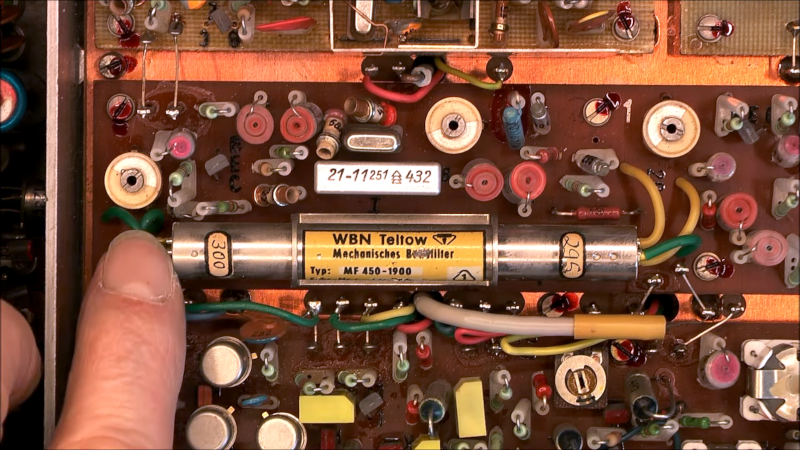

Of course, this technique will work anywhere you want to send images over a communication medium. Hams use these SSTV formats even on noisy shortwave frequencies, so the protocols are robust.

Hams used SSTV to trade memes way before the Internet. Need to receive SSTV? No problem.