The radio spectrum is carefully regulated and divided up by Governments worldwide. Some of it is shared across jurisdictions under the terms of international treaties, while other allocations exist only in individual countries. Often these can contain some surprising oddities, and one of these is our subject today. Did you know that the UK’s first legal CB radio channels included a set in the UHF range, at 934 MHz? Don’t worry, neither did most Brits. Behind it lies a tale of bureaucracy, and of a bungled attempt to create an industry around a barely usable product.

Hey, 2019, Got Your Ears On?

![Did this car make you want a CB radio? Stuurm [CC BY-SA 3.0]](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/1978_Trans-Am_bandit.jpg?w=400)

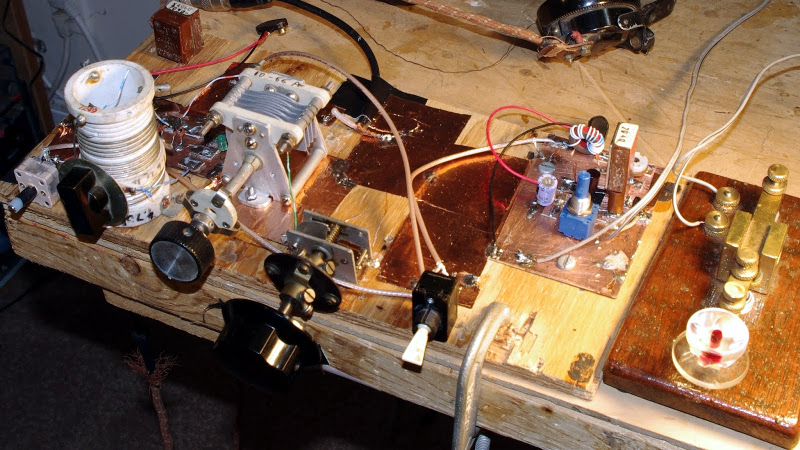

Mention CB radio in 2019 it’s likely that the image conjured in the mind of the listener will be one from a previous decade. Burt Reynolds and Jerry Reed in Smokey and the Bandit perhaps, or C. W. McCall’s Convoy. It may not be very cool in the age of WhatsApp, but in the 1970s a CB rig was the last word in fashionable auto accessories and a serious object of desire into which otherwise sane adults yearned to speak the slang of the long-haul trucker.If you weren’t American though, CB could be a risky business. Much of the rest of the world didn’t have a legal CB allocation, and correspondingly didn’t have access to legal CB rigs. The bombardment of CB references in exported American culture created a huge demand for CB though, and for British would-be CBers that was satisfied by illegally imported American equipment. A vibrant community erupted around UK illegal 27 MHz AM CB in the late 1970s, and Government anger was met with campaigning for a legal allocation. Brits eventually got a legal 27 MHz allocation in November 1981, but the years leading up to that produced a few surprises.

Governments tend to be their happiest when in the driver’s seat, and thus they were reluctant to simply licence the same CB allocation as the American one. During the protracted period of campaigning by CBers over the end of the decade it became obvious that there was a very significant demand for an allocation but they could not be seen to let the illegal CBers win. Their first tactic was to propose a 928 MHz UHF allocation with a 500mW power limit which was rejected by the CB lobbyists, so the final allocation became a 27 MHz one with a 4W limit on an odd set of frequencies incompatible with the American ones, and using FM rather than the American AM. Alongside this they clung to a UHF allocation, which was finally given at 934 MHz.

The result was that Brits had two CB allocations, one of which on 27 MHz that worked even if it wasn’t as good as the American sets, and one on 934 MHz that didn’t work very well at all and had eye wateringly expensive equipment. All the wannabe Rubber Ducks gravitated towards 27 MHz, but 934 MHz became an exclusive pursuit for enthusiasts; essentially another amateur band in which propagation and DX chasers plied their craft.

The Government hoped that having two CB allocations unique to the UK would create a home-grown industry supplying British-made CB rigs, a seductive idea for politicians with little knowledge of how the electronic hardware industry works. For example, the same idea has been touted in recent years as a reason behind drone licencing laws. But in reality, the market was soon flooded with UK-spec 27 MHz radios from Far Eastern manufacturers. By contrast 934 MHz rigs were rare, with only one or two models being brought to market. The object of desire was the Cybernet Delta One, a video review of which we’ve placed at the bottom of the page.

Christmas 1981, The Day The Dream Ended

If you were an AM CBer who bought a legal UK 27 MHz FM rig in November 1981, then life continued as usual as the community moved to the new band. They had a triumphant couple of months as victors savouring their spoils, but then Christmas came around, and everyone who’d sat in the cinema watching Convoy and fantasised about CB lingo got a rig of their own. Overnight the dream was shattered, followed swiftly by the UK CB bubble bursting as the novelty wore off. 27 MHz CB continues in the UK with a set of European channels now added to the UK ones, but never again will it be anything approaching cool.

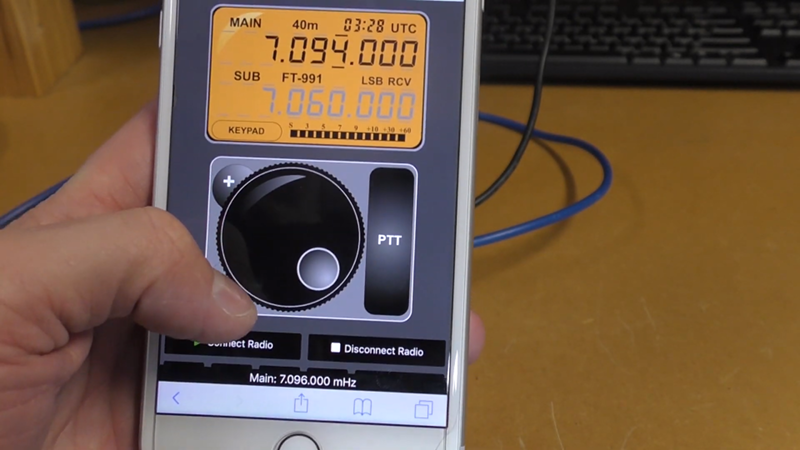

Meanwhile the 934 MHz channels continued to provide an experimentation ground for enthusiasts, and every month in Practical Wireless there was a column devoted to its propagation. In 1988 as the mobile phone industry began to expand, there was a demand for UHF frequencies, and the Government stopped the sale of new 934 MHz equipment. A decade later the allocation was officially removed, and those 934 MHz rigs are now illegal to use, though they do still appear in radio rallies from time to time.

The UK CB boom had a surprising effect, in that it brought a whole new audience into radio as a hobby and caused a corresponding boom throughout the 1980s as many of those people went on to obtain their amateur licences. If you meet someone with a G1 callsign there’s a good chance that’s the generation they came from, so ask them if they had a 934 MHz radio. Even if they didn’t, they’ll probably be able to tell you more about this interesting side chapter in radio history.

Now, sit back and enjoy M0OGY’s review of a 934 MHz radio.

your magic smoke. Even if you are lucky, stray parts are the root of boundless malfunctions from disruptive to deadly. [TheRainHarvester] shares his trick for

your magic smoke. Even if you are lucky, stray parts are the root of boundless malfunctions from disruptive to deadly. [TheRainHarvester] shares his trick for