Although we do often see projects that take antiques and replace some or all of their components with modern equipment, we can also sympathize with the view that (when possible and practical) certain antique electronics should be restored rather than gutted. [David] has this inclination for his 1948 GE radio, but there are a few issues with it that prevented a complete, period-correct restoration.

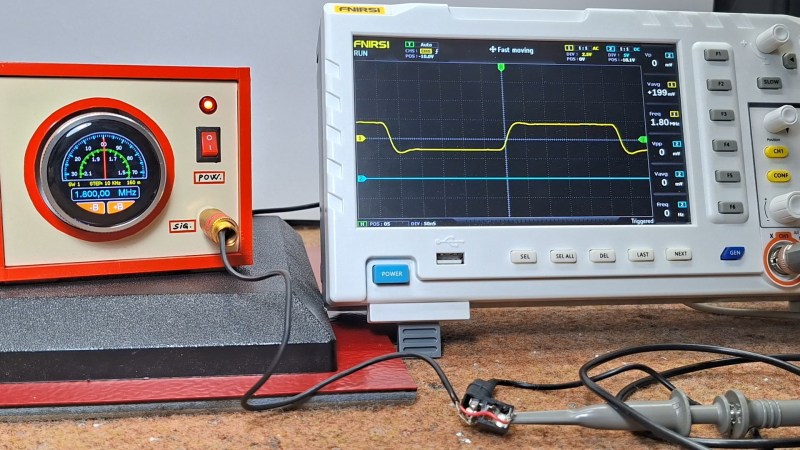

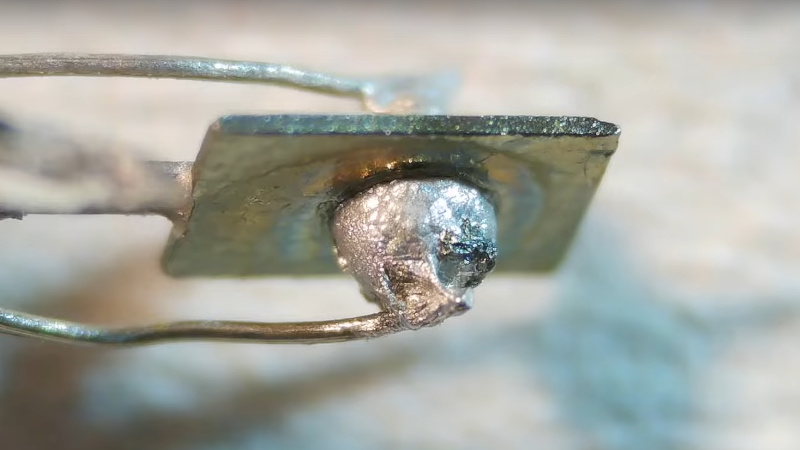

The main (pun intended) issue at the start of this project was safety. The original radio had a chassis that was just as likely as not to become energized, with the only protection being the plastic housing. [David] set up an isolation transformer with a modern polarized power cable to help solve this issue, and then got to work replacing ancient capacitors. With a few other minor issues squared away this is all it took to get the radio working to receive AM radio, and he also was able to make a small modification to allow the radio to accept audio via a 3.5mm jack as well.

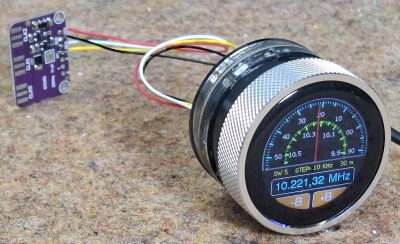

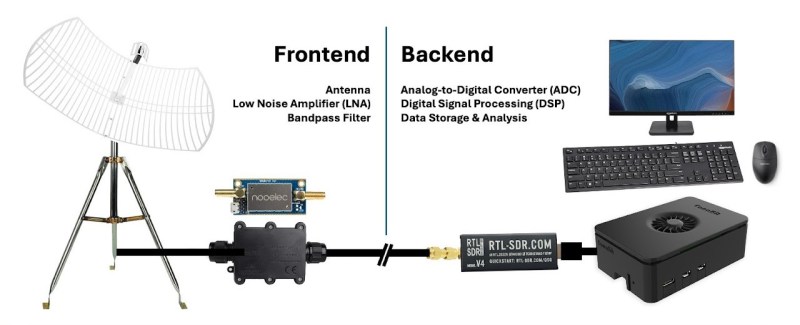

However, [David] also has the view that a period-correct AM transmission should accompany this radio as well and set about with the second bit of this project. It’s an adaptation of a project called FieldStation42 originally meant to replicate the experience of cable TV, but [Shane], the project’s creator, helped [David] get it set up for audio as well. A notable feature of this system is that when the user tunes away from one station, it isn’t simply paused, but instead allowed to continue playing as if real time is passing in the simulated radio world.

Although there are a few modern conveniences here for safety and for period-correct immersion, we think this project really hits the nail on the head for preserving everything possible while not rolling the dice with 40s-era safety standards. There’s also a GitHub page with some more info that [David] hopes to add to in the near future. This restoration of a radio only one year newer has a similar feel, and there are also guides for a more broad category of radio restorations as well.